Nearly six weeks after his surgery, the world’s second recipient of a genetically modified pig heart has died, the University of Maryland announced Tuesday.

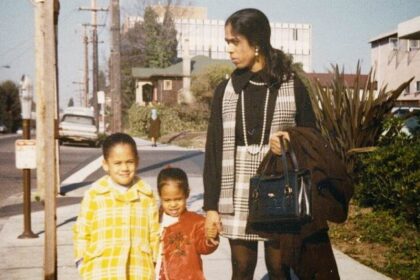

Lawrence Faucette, a 58-year-old resident of Frederick, Md., with terminal heart disease, died Monday. He had received the experimental xenotransplant on September 20 at the University of Maryland Medical Center in an eight-hour operation.

After his surgery, the Navy veteran and former vaccine researcher at the National Institutes of Health made “significant progress,” according to a statement issued by hospital officials. He was able to do physical therapy, spend time with his family members and play cards with his wife.

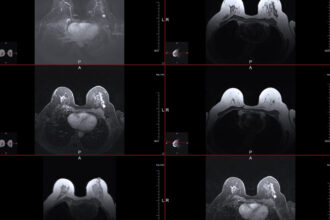

However, in recent days, Faucette’s heart began to show initial signs of organ rejection, though some of the genetic changes made to the heart were meant to reduce the risk of the recipient’s immune system attacking the pig heart.

“We mourn the loss of Mr. Faucette, a remarkable patient, scientist, Navy veteran, and family man who just wanted a little more time to spend with his loving wife, sons, and family,” said Bartley Griffith, director of the cardiac transplant program at UMMC.

When Faucette came to UMMC, he was in end-stage heart failure and his heart stopped twice before the surgery. He required resuscitation shortly before the surgery. He was deemed ineligible for a traditional heart transplant and on September 15, the Food and Drug Administration granted emergency authorization for the experimental surgery.

Last year, the same medical team performed the procedure for the first time on a 57-year-old patient named David Bennett. But after 40 days of improvement, he took a turn for the worse and died not long after, two months after the xenotransplant — possibly from an infection caused by a pig virus.

The hearts used in both xenotransplants came from pigs that have been genetically engineered by a biotech company called Revivicor, which sees xenotransplantation as a solution to the shortage of human organ donors. They have 10 changes to their DNA to make their organs better suited to residing within a human body, which include inactivating a growth gene — so the porcine heart won’t continue to expand after transplantation — and removing molecules most likely to provoke an immune attack.

The medical team said it hopes to learn from the experiences of both men in order to identify factors that can be prevented in future transplants.

Faucette’s wife, Ann, said in a statement that “he never imagined he would survive as long as he did, or provide as much data to the xenotransplant program. He was a man always thinking of others, especially myself and his two sons.”

The family, she said, looks forward to advancement and success in the field of xenotransplantation.