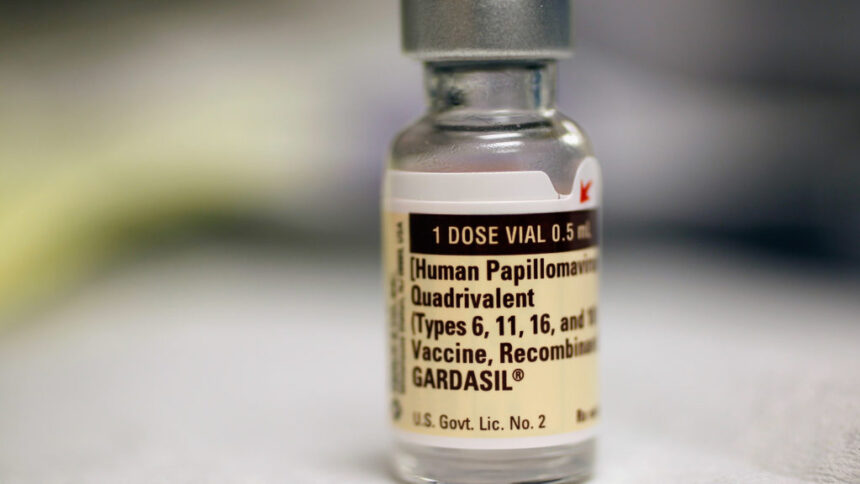

Vaccines work well to prevent cancers caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV). So well, in fact, that it may be time to review HPV screening protocols, according to the somewhat provocative conclusion of a new study examining the occurrence of genital HPV types eight years after immunization, published Wednesday in Cell Host & Microbe.

The randomized controlled study included more than 60,000 women from 33 Finnish communities born in 1992, 1993, and 1994. The study randomly divided them into three groups based on their cities’ HPV vaccination strategies: gender-neutral HPV vaccination, girls-only vaccination, and no vaccination. The researchers then followed up four and eight years after the vaccination to test for 16 types of genital HPV — HPV 16/18/31/45, the high-oncogenic types, and 12 other types carrying lower cancer risk.

The researchers were looking to establish the most effective immunization strategy, and to determine what happens after a successful vaccination effort significantly depleted high-cancer-risk HPV types 16/18/31/45.

“This paper nicely paints a picture that indeed the vaccine is most efficient when you vaccinate boys and girls. We can see how the different HPV types are distributed in the communities where you have both genders vaccinated, so it is clear that there’s a stronger protection,” said Ville Pimenoff, a senior researcher at the Karolinska Institutet and professor at the University of Oulu in Finland, who was the study’s lead author. “Apart from the individual vaccination, then you have the herd protection.”

In the group with gender-neutral vaccination, a 50% vaccination coverage per year cohort was sufficient to nearly eliminate the occurrence of high-oncogenic HPV types targeted by the vaccine. When vaccines are administered exclusively to girls, the uptake needs to be extremely high to reach the same results. Further, HPV45 depletion was observed only in the gender-neutral group.

“Girls-only vaccination for HPV herd immunity requires 90% of girls to be vaccinated year on year since only half of the population is being protected, but immunizing boys starts to protect the other half of the population and the virus has nowhere to go,” Margaret Stanley, emeritus professor of epithelial biology at the University of Cambridge, who was not involved in the study, wrote in a commentary provided via the Science Media Centre.

At the same time, the samples showed that other HPV types closely related to those targeted by the vaccine had replaced the initial targets. This is not surprising, said Pimenoff: When you have significant variety in a virus type, as with HPV, removing a subset of it leaves a niche that is free to be easily occupied by the remaining strains, which have evolved in a similar way.

“I think this work confirms the added value of gender-neutral vaccination and directs a need to be dutiful in monitoring changes in non-vaccine type distributions. It is impossible to know whether the latter will yield any significant threat but the risk is probably very low,” said Peter Stern, a professor of immunology and cancer biology at the University of Manchester, who was not involved in the study.

Pimenoff said the findings of his study suggest it may be appropriate to rethink screening practices. In a population like Finland’s, he said, there is now a cohort of women who are coming to screening age (which starts as early as 25, depending on the municipality) and have been vaccinated against HPV in their teenage years. Based on the study’s findings, low-risk HPV varieties are likely to be detected in these screenings. “So suddenly you have a reasonable number of women who at the screening are positive for HPV [types] which are included in the screening protocols typically, but are low risk. If you follow the standards of screening, those are considered positive, to be followed up on,” said Pimenoff.

HPV 33/35/52/56/58/66 are included in screenings as they are listed by the National Cancer Institute as high-risk, because they have been associated with malignancy. Yet the chances of them leading to cancer are much lower than the targeted types, and though there could be a concern that they may eventually become more oncogenic, the data so far doesn’t suggest they will.

“We also see that in these women who have had in our cohort initial low risk type infection after vaccination, there is no sign of any progress,” said Pimenoff. “So in that sense, the data points that the risk is very low or doesn’t exist.”

With such low-risk scenarios, the potential downsides include overdiagnosis and a waste of public health resources that could be redirected elsewhere — not to mention requiring women to undergo unnecessary testing, such as additional Pap smears.

If screening post-vaccination becomes limited to high-oncogenic types, doing it less often would be sufficient, said Pimenoff — perhaps once every 10 years. He noted, however, that recommendations can’t be the same everywhere, as “each country has their own status and a system on how to handle vaccination, how they handle screening, and the whole situation of what is the vaccine coverage.”

In the U.S. in 2021, for example, 59% of adolescents between the ages of 13-15 had received two or three doses of the HPV vaccine according to recommendation guidelines, according to the most recent available data.

Other researchers expressed more caution about the prospect of changing screening guidelines. “I do not think there are any immediate implications for screening or vaccine uptake. There are differences in gynecological practice in the USA which some might say lead to a lot of over-treatment but the results here will not impact this issue significantly,” said Stern.

Still, the size and design of the study — particularly the fact that it included non-vaccinated cohorts, which are practically absent now in Finland — mean that it’s likely to be relevant for future policy discussions. “While we should not rush to change screening policy as a result of one study, it would be prudent to check if these results are replicated elsewhere, and to consider the implications for which populations we screen and how we screen them,” Stephen Duffy, professor of cancer screening at Queen Mary University of London, via said in a statement via the Science Media Centre.